INTERVIEW and EXCERPT

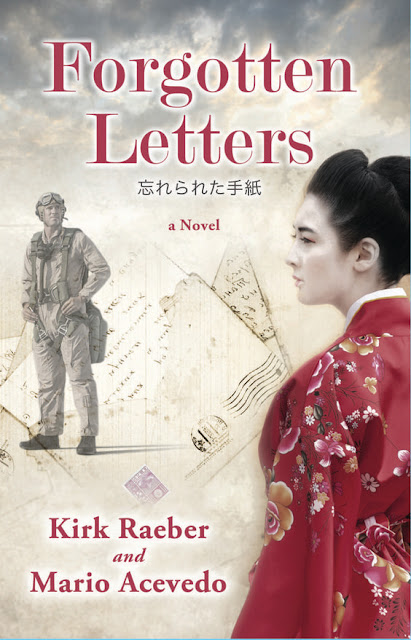

Forgotten Letters

by Kirk Raeber and Mario Acevedo

Author Kirk Raeber stops by today for an interview and to share an excerpt for his book, Forgotten Letters. Keep an eye out for my review, coming soon. This blog post is brought to you by Kate Tilton's Author Services.

Description

A trove of forgotten letters reveals a love that defied a world war.

In 1924, eight-year old Robert Campbell accompanies his missionary parents to Japan where he befriends a young Makiko Asakawa. Robert enjoys his life there, but the dark tides of war are rising, and it won’t be long before foreigners are forced to leave Japan.

Torn from the people Robert has come to think of as family, he stays in contact by exchanging letters with Makiko, letters that soon show their relationship is blossoming into something much more than friendship.

The outbreak of total war sweeps all before it, and when correspondence ends with no explanation, Robert fears the worst. He will do anything to find Makiko, even launch himself headfirst into a conflict that is consuming the world. Turmoil and tragedy threaten his every step, but no risk is too great to prove that love conquers all.

Forgotten Letters is a Book of the Year INDIES 2016 finalist and International Book Readers' Favorite Award winner.

Book Video

Excerpt

Chapter 1

April 1980

My parents’ rental home in Franklin Park is just as I remember it. Unfortunately. Old. Dilapidated.

I want the house to have changed, to be a symbol of transition, of progress, a launch pad from the misfortune that piles around me. Instead it anchors me to a past and a present that I want to shake free.

Last year, Mother had been diagnosed with leukemia. Father died of a stroke shortly after hearing the news. His passage accelerated her condition, and they died ten months apart. He was 64, she was 59.

But I don’t just grieve for them, I also grieve for myself. One month after we laid Mother to rest, I learned that my husband Eric cheated on me. Our marriage had been under a lot of pressure, mostly because of finances. My way to cope was to draw inward. His way was to find comfort with someone else. Now, ironically, with the passing of my parents and the inheritance that has come my way, our money woes have eased. But Eric and I are still convulsing in the throes of remorse. We need an escape from our shared, self-inflicted misery.

Unlocking the front door to the house, I push it open to a bloom of stale, musty air. What a dying marriage smells like, I tell myself.

My brother Ichiro lingers behind me on the porch steps. He does a lot of that: Lingering. Hesitating. Stalling. Sadly, he’s twenty-five years old and hasn’t yet finished college or had a decent job. It’s like he’s got an anchor stuck in the mud and won’t break the chain, preferring to drift in circles as the tide of life shifts around him.

I know the reason. He hates being Japanese, and he’s meandered through life like he’s trying to find his true soul. When he was in school elementary, playground bullies made fun of his name and nicknamed him Itchy. Now he insists on being called Kyle. Says it makes him sound like a true-blue American. Then as the Vietnam War raged, which happened during his childhood, other boys taunted him with “gook” and “dink” even though he doesn’t have a drop of Vietnamese blood and is half American. Plus every Pearl Harbor Day brought another round of insults. Despite having been born here with no memory of Japan, mom wouldn’t let him forget where his roots came from. She would only converse with him in Japanese and taught him how to read and write using kanji.

“Kyle,” I say, “come on.”

He lifts one earpiece of his Walkman, asking, “Huh?” like he has no idea what we are doing here.

“Inside,” I order.

The small foyer opens to a large front room. Filmy light beams through dirty windows. Faded rectangles on the dingy walls mark where pictures once hung, and wispy cobwebs dangle from the overhead lights.

Ichiro trails at my heels, heavy metal buzzing from his headset. He nods and taps his fingers to the rhythm. In their will, my parents divided the estate between Ichiro and me, but they wisely named me as the executor. Otherwise nothing would get done.

Pad and pen in hand, I wander about the first floor and the basement, cataloguing what needs attention before we list the house for sale. More than a decade of assorted renters have left their mark. Mismatched paneling and skewed electrical outlets show sloppy repair work. Stained and spongy drywall indicates plumbing leaks. Abandoned junk lies piled in the basement. The house has changed since we lived here, but the changes are all in the wrong direction.

Thinking back to our times here I want to sink into a state of reverence, to let memories swirl around me. But resentment over Eric eats me like acid, and I’m not a Pollyanna to ignore that my marriage problems are leaving me hollow with anguish.

Ichiro doesn’t do much but trail behind me. We make our way to the steps leading upstairs. Dust bunnies scatter around our feet.

He mashes the Walkman’s off button, yokes the headset around his neck, and brushes long bangs off his forehead. A loose black The Deviants t-shirt shrouds his gangly frame. With his shaggy raven hair and high-cheek bones, he looks so much like mom, except for his gray eyes--our father’s gem-like eyes. Meanwhile I have inherited a bony Irish-Norwegian frame. Thank you very much, Dad.

Ichiro’s eyes sparkle with surprising curiosity. “We really have to sell this place?” He stares at the empty front room, no doubt imagining where to drop a thrift-store sofa for his deadbeat buddies to crash on.

“We don’t have to do anything,” I snap. “But unless we do something, nothing will ever get done.”

Ichiro raises his hands and retreats a step. “Fumiko, chill already. You got problems, don’t take them out on me.”

Point taken. I loosen my bitch armor and climb the stairs.

Halfway up, Ichiro says, “Hey, Sis...”

I retighten my armor. The only time Ichiro starts with, “Hey, Sis,” is when he wants to mooch cash. He’s already received his half of our father’s insurance--minus mom’s medical bills. Even though Ichiro is as indifferent to his finances as he is to his appearance, I can’t believe he’s already squandered forty-thousand dollars.

Clenching my jaw, I refuse to turn around and look at him. The steps sag and creak beneath me. Damn, more repair work to get done.

“Sis,” he continues, “do you think mom’s cancer had anything to do with Hiroshima?”

Stunned, I hitch a step, then proceed to the top of the stairs. His question treads into forbidden ground, for our parents rarely mentioned their wartime experience.

We knew mother was at Hiroshima. Every August, she received a paper origami crane, folded inside an envelope with a letter from the Japanese government to the survivors of the atomic bombings. Her eyes would mist and without explanation, she placed the crane on a bookshelf. Ichiro or I would play with the crane until it was reduced to a smudged, limp mess, then it and the envelope and letter disappeared.

We were like all kids, focused only on life as it unraveled before us. Even though I was fluent in Japanese, I never bothered to read the letters. I sensed they were something private. Besides, whenever Ichiro or I asked either mother or father about the war, their answers became vague and evasive. If our parents wanted their past hidden, it stayed hidden, remote. So remote that when mother was diagnosed with leukemia, none of us bothered asking if it might be related to her exposure to the A-bomb’s radiation.

“Well?” Ichiro insists.

I stop on the landing and gaze at him. “I don’t know.”

His expression dulls, perhaps disappointed because I--always Miss Smarty-pants with something to say--have nothing.

He gives a resigned shrug. “I guess it doesn’t make a difference, does it?”

“I guess not.”

We stare at each other, hesitating, uncertain. I feel like my brother is drawing me into his world. I snap my fingers. “Let’s get back to work.”

After inspecting the second floor and noting with dismay the battered doors, threadbare carpet, and cracked bathroom mirror. Now that I’ve done with my chores of inspecting the house, nostalgia presses heavily on me. Memories tug at my heart, and the loss of my parents seems again fresh and painful.

I look for Ichiro. As usual, when there is work to be done, he has ditched me. I am about to call for him when he clatters up the stairs, a stepladder perched on one shoulder.

“What are you doing?” I ask.

He slips the ladder off his shoulder and drags it to the middle of the hall. He points up to a trapdoor in the ceiling. “The attic.”

Yep, I missed it and am astonished that Ichiro noticed.

He glances at his watch and says, “I know it’s late but let’s take a quick look-see.”

I study the trapdoor. “Depends on what we find, it might take a while.”

“Whatever.” He steadies the ladder.

“Why don’t you go first?” I ask.

“You’re the oldest. And you have the flashlight.”

“All right.” I hand him the pad, then climb the ladder until I can touch the trapdoor. I ascend another step for leverage. The door budges on the first push. I lift and swing it aside to reveal a dark, spooky void.

Raising my head, I first look for spiders and anything that can jump on me. Deciding I am safe, I aim my flashlight, but the gloom swallows the beam. A wooden spool hangs on a cord just over the opening. Climbing another step, I clasp the spool and give a tug. A switch clicks, and a bare bulb ignites.

The bulb’s yellow light turns gray as it extends into the reaches of the attic. I scramble up onto the floor and stand, careful not to bump my head on the slanting rafters. Ichiro joins me, and as we slough dust from our pants, we scope out the boxes and junk heaped against the walls.

He approaches a pile of antique table lamps. Picking one up, he whisks its tasseled shade and glass base. He puts the lamp down and examines the others, stroking his chin as he thinks. “Vintage,” he says. “Authentic art deco.”

His pronouncement surprises me. I didn’t think my brother cared about anything except getting by with as little effort as possible.

I pan a disapproving appraisal at the rest of the clutter. Even if Ichiro is right in assuming we have some treasure here, I’m not willing to spend a lot of time rummaging through these abandoned odds-and-ends before calling it quits for the day.

Calling it quits. The thought whipsaws through my brain until it congeals into an image of Eric and me. I don’t want to quit our marriage but the space between us is a minefield of recriminations and pain. What can I do? How can I forgive?

Tears threaten my eyes, and I squeeze them with my fingers.

My sadness ebbs, and when my mind returns to the present, I see Ichiro sorting through an old wooden carpenter’s box filled with tarnished and rusted tools.

“I’m tired,” I say. “If you want to pick through this stuff, we can come back tomorrow.”

Ignoring me, Ichiro makes his way around the periphery of the attic, halting to inspect whatever catches his fancy. I approach a dresser pushed against the far wall. I have a friend who restores furniture and she might like this piece. Searching the drawers, I find only old receipts, coupons, notes, broken pens. Behind the dresser rest cardboard boxes stacked on a footlocker. I pivot the dresser aside and peek inside the boxes. They are filled with moldy newspapers and Life magazines, sprinkled with mouse droppings.

“What have you got?” Ichiro looks over my shoulder.

“Trash,” I answer.

We set the boxes to one side, and he drags the footlocker out of the shadows. It thumps heavily across the floorboards. Because the battered locker is olive green, I’m ready to declare it military surplus and packed with God-knows-what-crap until I read what is written on the lid. Stenciled in faded white paint is: Robert S. Campbell, Captain, U.S.A.A.F.

Ichiro stares. “This was dad’s?”

Dad didn’t talk about his military service. “Seems to be. He was in the war.”

“A.A.F? He was in the Army Air Force?”

“I guess.” Taking a knee beside the front of the locker, I try the catch but it’s either locked or frozen.

Ichiro leaves my side and returns with a hammer and a large flat-tip screwdriver from the toolbox. Kneeling in front of the locker, he jams the screwdriver into the keyhole and twists. Nothing. With the hammer, he pounds on the back of the screwdriver, then levers the screwdriver until the lock clicks. The hasp springs open.

He drops the tools, undoes the end latches, and lifts the lid. We both lean in to see.

After so much effort on Ichiro’s part, I imagine he expects to be rewarded with the dazzling glow of jewels and golden coins. But inside rest more newspapers and a large manila envelope, marked with hand-written script: Campbell, R.S. CPT. 20th Air Force.

The envelope contains typewritten military orders, many on brittle onionskin. The newspapers--Chicago Daily Tribune, Los Angeles Herald-Express, Asahi Shinbun--are copies dated from 1946 through 1965.

Beneath the newspapers lay two garments wrapped in paper. I open the first. It’s a precise rectangle of fabric, that I unfold into a kimono, of cream silk with red brocade and embroidery, folded into. Mom’s wedding garment.

I blink at the kimono, astonished that it still exists. I last saw it the day mother married our father, before Ichiro was even conceived.

“What it is?” Ichiro nudges me.

I wake from my reverie and say, “Mom’s wedding kimono.”

“Oh,” he mumbles. “It’s pretty.” He runs his hand across the textured silk.

When I open the second package, out wafts the faint odor of mothballs. I unfold a uniform coat, in olive-drab wool. Sewn to the left shoulder is a round blue patch embroidered with yellow wings and a small red circle inside a white star. The metal insignia on the lapels and shoulder straps are darkly tarnished, but the colorful ribbons above the left pocket remain bright as new. Pinned above them is a large set of wings, the silver black with age.

Ichiro takes the jacket. He fingers the wings. “Dad was a pilot?”

Another detail that I don’t know. I shrug. This is like excavating a sarcophagus, brimming with mystery and wonder. We discover framed photographs. One is a black-and-white, of my pretty mother in a western dress, her belly swollen with Ichiro, me in a dark skirt with a white petticoat, white gloves, and a matching hat. My handsome father, dashing in his pinstripe suit and spectator shoes (why don’t men dress like this anymore?), leans over mom’s shoulder to smile at the camera. The kanji script along the bottom reads Matsuda Photography Studio. The memory of that day crashes though my mind, and I swoon and catch myself before I topple over.

If Ichiro noticed my reaction, he doesn’t show it. Instead he rises and slips his arms through the sleeves of the jacket. It drapes baggy, past his hips. On dad it would’ve hung to his waist and fit snug around his muscular shoulders. Ichiro leaves the jacket unbuttoned and twists from side to side. “Whaddaya think?”

The contrast between the magnificent jacket and his Converse high tops and his thin legs in their frayed jeans makes him look childish and ridiculous. But I answer diplomatically. “I’ve never seen you this dressed up.”

He kneels back down, and we continue to dig through the footlocker, unearthing more and more of our parents’ past.

“Careful,” Ichiro warns. “I have a friend who poked through his parents’ stuff only to find Polaroids of them at swinger parties.”

I blush. Though certain our parents were not wife-swappers, I now have questions as to why they kept so much of their lives stashed away.

Another photo. One of dad in sweat-stained khakis, a headset draped around his neck, its cables dangling down the front of his shirt, pilot’s wings pinned above the left pocket. Smiling, he stands with three other aviators huddled in the shadow beneath the wing of an enormous airplane.

My parents’ history is such an enigma. I remember glimpses from my early childhood, but not enough to piece together what I’m finding.

In one corner of the locker I discover a box about the size of two shoeboxes placed side-by-side. Red foil covers the box, the top secured by a white silk ribbon squashed flat. Surely, it contains special secrets. But who keeps a box of such secrets?

I lift the box out of the footlocker and center it on old newspapers to protect it from the gritty wooden floor. I tug at the knot until the ribbon falls away.

Ichiro presses close as I remove the lid. Inside lay rows of letters, yellowed and stained.

The letters are in random order. I thumb through them, admiring the variety of stamps. The earliest postmark is 1930. I pick one with a postmark dated April 1952. The return address is in Japanese and English, from Makiko Arakawa--mother’s maiden name--in Yokohama. It’s addressed in both languages to Robert Campbell, to his parent’s home here in Chicago.

Delicately, I open the flap, slide the letter out, and unfold the stationary.

The script is in Japanese, written in faded blue ink.

I read aloud, “Dear Robert...”

[Want more? Click below to read a longer excerpt.]

Praise for the Book

"The book is a page-turner...The writing is excellent and draws you right in. You can see that the author knows his stuff about Japan, and about the consequences of war. The descriptions are very good and, as a lover of Japan myself, I could not find any faults." ~ Kim Anisi for Readers' Favorite

"The book is incredible. The story line drew me in and I was hooked almost immediately. I loved the Campbells and the Asakawas, and couldn't stop reading until I found out where their paths were heading. Such a wonderful story." ~ Lindsay Olson

"Even in the darker moments, the message that remains throughout is one of hope, that love will always overcome suffering. This is a book I would recommend to book clubs, WWII history-buffs and romantics alike." ~ R.J. Rowley

"Great read - well paced with steady progression of action and character development leading up to a thrilling conflict. Would strongly recommend as a book that not only presents complex and interesting characters, but also gives excellent insight into life in Japan during WW II." ~ Aj

"Great read. Really enjoyed it. Hard to put down, storyline was very suspenseful. Great mixture of history, painting a realistic image of mid 20th century Japan, along with a powerful love story." ~ Peter Jost

Interview With the Author

For what age group do you recommend your book?

Forgotten Letters is recommended for anyone old than 18 years. I think the story appeals to both women and men.

What sparked the idea for this book?

The story was a dream I had over 15 years ago. The entire story beginning, middle, and end was in my dream.

So, which comes first? The story or the characters?

The story came to me at first and then the characters were developed as the book was written.

What was the hardest part to write in this book?

The hardest part was getting over the idea that I could start a book writing project.

How do you hope this book affects its readers?

How long did it take you to write this book?

It took me four years

What is your writing routine?

I had the help of a ghost writer Mario Acevedo, who was very good. I worked on the book daily.

How did you get your book published?

I had to self publish because I am an unknown. I sent numerous requests to agents but without any interest from them.

What advice do you have for someone who would like to become a published writer?

I have had a great deal of fun and learned a lot. Keep working and never give up your goal of publishing a book.

What do you like to do when you're not writing?

I enjoy working in the yard and taking care of 12.5 acres.

What does your family think of your writing?

They are all very excited and proud.

Please tell us a bit about your childhood.

I grew up in Denver, Colorado. I loved the outdoors and would ski in the winter and camp in the summer.

Did you like reading when you were a child?

Not really, it was not until college that my interest in reading and learning started.

Do you hear from your readers much? What kinds of things do readers say?

Everyone who has read Forgotten Letters really loved the story and asked me when the next book is coming out. They also say things like "very easy read", "I could not put the book down", "amazing story", and "when will the movie come out?"

What can we look forward to from you in the future?

I am working on a children’s book.

Thank you for taking the time to stop by today, Kirk. Best of luck with your future projects.

About the Author

Kirk Raeber is an emergency room physician. He has always had a strong interest in World War II history and especially in the war in the Pacific. He served in the US Navy and was stationed in Japan for one year. Forgotten Letters is his first novel. He lives in California with his wife.

Links