REVIEW and EXCERPT

When a Bulbul Sings

by Hawaa Ayoub

When a Bulbul Sings by Hawaa Ayoub has just been released. You can read my review and an excerpt below. Please check out my previous blog post for my interview with the author.

Description

When Eve, a highly intelligent fourteen-year-old British girl, is taken by her parents to a remote mountainous Yemeni village where life has remained the same since ancient times, she is forced to marry Adam and her life becomes a dystopian novel caught in a real-life limbo. Her constant attempts to escape the mountains are not only hindered by the treacherous terrain, but her Uncle Suleiman, who planned for her marriage since first setting eyes on her, keeps her captive to ensure his son sends him a monthly allowance.

Eve’s captors want to subdue her strong personality, and individuality; Eve is put under pressure to be like all the girls, to be a woman not a girl. She struggles with the way of life, but also the mentality and culture. She fights for her freedom, but her captors’ constant criticism chip at her spirit. Eve is set on returning to Britain to resume her education before she misses her chance at university, before her genius is wasted, but Uncle Suleiman’s addiction and greed give him an equally strong determination to prevent her from leaving. She witnesses forced marriages and child marriages as well as Female Genital Mutilation (FGM). She lives amongst a beautiful people in an intriguing ancient culture, but the beauty of her surroundings jar with the ugliness of captivity where her freedom has been confiscated and she becomes Uncle Suleiman’s hostage.

This is the story of Eve and her fight for freedom. It is a story about the inequality, injustice, and violations of human rights millions of girls around the world face due to their gender when forced or entered into underage marriage as child brides.

Excerpt

Chapter One

IN THE BRIGHT, WHITE SUN, BORDERED BY PALM TREES WITH curved trunks and green heads that seemed to bow, and acacia trees whose green boughs shivered in the heat, men and women gathered in and around Uncle Faris’ house made up of many rooms each standing separately around a large yard; most were locals from The Dibt (a semi-arid, semi-desert like area scattered with palm trees, Thorn of Christ trees and various euphorbias), and many had come in a procession of cars from the high southeast mountains which deceivingly looked like tiny mounds in the far distance from here. All were guests, dressed in their finery: men in white dresses with red and white shawls over their shoulder blades, curved daggers around their waists, rifles over the shoulder; women adorned with gold, in an array of coruscating fabrics, bright and dark, sequinned or glittered; all merry and in good spirit. Drums beat, reed pipes blared with an African-Arab descant and merry men danced in lines, the silver of their dagger Jambias glinting in the sun, outshone by the flash of teeth in laughter. The handsome groom, wearing black western trousers, a white shirt and black tie, who had come down from the mountains to take his beautiful bride by her delicate hand and lead her to her new home, danced and smiled; his fair countenance contrasted by his black hair, moustache and eyebrows now looked worried as the bride was not being cooperative, in fact his three relatives (two sisters and an Aunt) were dragging the poor girl across the length of a narrow windowless room, where they had been preparing her. Eve, small and slender, whose long loose curls of wavy brown-black hair and beautiful olive skin were concealed; fourteen years old (and usually intrepid and vivacious) and now afraid of what was happening looked around her, but her peripheral view was obstructed by the long black hood and veils forming the top part of her shiny black sharshaf; her brown eyes gleamed with tears from above the scarf they had tied around her face from the nose downwards, alarmed at the large crowd which had gathered around them to watch the giving away of the bride. Father’s lips trembled and his nose ran as he took her small right hand and placed it into the groom’s for the second time, as she had snatched it away the first. In Welsh accented English, jarring with the exotic Middle East environs and garb, she begged not to be forced to marry; Father, though his eyes betrayed unhappiness, bit his lower lip and pulled her forward towards the groom again whom now held her tightly using arm and elbow to keep the fey, finicky bride clasped beside him, whilst his sisters and Aunt helped keep her gripped. This simply could not be happening, she wasn’t even supposed to be here and should have been long back in Britain instead of missing two months of school following the Christmas holiday. Automatic rifles were held above her shoulder by the Uncles in turns and the tremendous bangs left her ears ringing. Were they threatening her? Well they had succeeded, scared out of her wits she called out in English for her eldest brother to save her, but her voice was lost amongst the shrill vibrating screams emitted by all the women, ululations of an unwanted celebration. Poor Eve, she didn’t know this was just celebratory customs, shooting into the air by guests were expressions of joy, his Uncles shooting from close proximity to her head signified their pride she was joining their family (never mind it worsened her already throbbing headache). Presently they were standing in front of a Land Cruiser with a driver already waiting behind the steering wheel, the groom got in and extended his hand towards her to join him, but she turned towards her father beseeching him from her heart, accompanied by a torrent of tears, to stop this madness. As she stared at him with her brown burrowing, hurt-doe eyes she remembered, and he remembered, how they got here and none of it made any sense to our bewildered bride.

*

SHE’D HAD A VERY HAPPY AND NORMAL CHILDHOOD, BORN AND BRED in Wales; she was Father’s pride and joy being such a well-behaved girl and having an extremely high intellect, and he constantly rewarded her exceptional behaviour and studies with lavish gifts.

Always the first to awake in the family, she watched the light chase out the darkness from the window where she had pulled an armchair and plopped her law books, waiting to hear the first part of what she enjoyed, and there it was: the loud, incessant bird song coming from the crown of a large oak tree emerging from behind the houses opposite. Their music filled the air, and as she closed her eyes she felt their whistles, chirps and trills vibrate in her temples and soul, and resonate throughout her body—their melodies so clear, energetic and full of the promise of life—as was she. Father always joked that she awoke early so as to cram as many activities she could into one day, and it was true for she had zeal to do everything: study, read books of all types, newspapers (her reading age was much higher than her chronological age), she explored the city she lived in, its rich green areas and urban alike, played the guitar, rode bicycles and played with her friends. But more than anything her whole direction was aimed at getting into university, and she wasn’t waiting until she got there to be enlightened; Mr. Halfspan (secondary school headmaster) and his deputy were in no doubt she would get into Oxford and were extremely proud of their star pupil; the brightest in One-Alpha-One (the highest set in her year), teachers were always impressed by her well of knowledge and the outstanding quality of her work. Now we don’t want you to get the wrong impression of our Eve, she wasn’t one of those nerdy children who are all study and no play, though she had been bestowed with, and nurtured, exceptional intelligence, she did not behave like an adult, but was a normal, popular girl with many friends, indulging in games and interests of her peers and pulling off practical jokes on her teachers. But there was nothing she wanted to be other than a lawyer. In the future Eve would ponder about many things in retrospect: she had begun to read law books while still in junior school; in both infant and junior school she had been advanced skipping whole years due to her high IQ; it seemed she was in a hurry to get to her future and the school was pushing her forward and she would have started secondary school very early had not the newly promoted headmistress put an end to it: citing, and garnering support, it would put too much pressure on Eve and be detrimental to her well-being (although little Eve was not under any pressure at all, she absorbed the curriculum and sailed through it with speed and ease, working at a much faster pace than the kids older than she in their class year) so she waited extra years languishing in Class Five until friends of her own age caught up with her. Although it would possibly not have changed the current course of things (well, who knows what knock-on effect one action has upon one’s future), Eve often wonders if the headmistress hadn’t interluded getting an early start in secondary school, if she would have made the same pace of progress and arrived early at University thus if she would have avoided the whole debacle she was in now (well, Eve—you’ll never know so stop torturing yourself).

Father had surprised them all when he said they would be holidaying in the country of their origin—Yemen. For reasons obscure then, but obvious now, both parents had kept them in the dark about their roots; and had not corrected the children’s misguided belief they were from Saudi solely based on receiving letters from their eldest brother from the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia—he lived and worked there. It was both surprising and intriguing to hear they descended from unheard of Yemen, and better still they were going to visit and experience the different culture—oh, this was a country not any of her friends had been to! The photos she would take, the stories she would bring back, and gifts for her friends. Lordy dordy, she could not wait to get there (if only she knew what was awaiting). Father chose the travel date for three days after her fourteenth birthday; brimming with eagerness and prepared for seeing exotic scenes, our fourteen-year-old had the excitement of a bus-full of tourists (safe to say that excitement has dulled considerably after the unfolding events not long after their arrival in Yemen). After leaving the small dusty and very chaotic Sana’a airport they swerved down wide dirt roads, swerving because the taxi driver engaged in conversation with Father would let go of the steering wheel and turn towards the latter emphasising with his hands what his mouth was probably perfectly imparting, while the children shouted at him in English to hold the steering wheel and watch where he was driving (he did not speak English, but understood the tone of panic).

Along the way they were stopped by a dark haired, bullet-strip-chested, automatic-rifle-shouldered young man; the children had only known the safety and security of stable Britain and were not used to seeing soldiers in the streets. Father handed over the passports, Eve guardedly glanced at the soldier and back at her father while another soldier was peering through the back-seat window; she had only seen people dressed like this, armed like this, on the news in some foreign country where guerrillas were rebelling against their government; and now Father had brought them to a country at war where guerrillas could stop people—maybe even shoot them. No amount of reassuring Eve would convince her they were soldiers, that they were not seventeen years old as she had estimated, but fully-grown men; there was no war it was only a check point. Eve wanted the taxi to turn around and take them back to the airport, but Father wouldn’t have it, instead he translated her worries to the taxi driver whom found it hilarious, tilting his head backwards, laughing his heart out, and glancing at her through the rearview mirror before laughing some more.

It seemed they would never find a room as all hotels had been filled due to the exodus of Yemenis from Saudi Arabia. Finally they were in a stark marble floored room and while Father went to get lunch she convinced her brothers there was a war and they should leave (by pointing out if there was no war there would be no need for soldiers in the streets with all that ammunition (she knew nothing about the Middle East)) a terrible feeling (intuition my dear) from the pit of her stomach was screaming at her to go back home immediately, and upon Father’s return even seventeen-year-old Yusef and fifteen-year-old Sami were clamouring to be taken back to the airport immediately. Father was able to reassure the boys, but Eve refused to eat and when Father extended a bottle of coke to her, she slapped it out of his hand; the brothers froze as the bottle shattered to pieces upon the marble floor. Mother’s face greyed and grimmed with foreboding, for she had reason to dread: during Eve’s happy, and unfinished, childhood there came a period of change in how Father treated her; she had gone from being his spoilt and beloved daughter to becoming his object of abuse: belting her, whipping her with tomato canes, calling her terrible names; and all unjustified for she had not changed, she had not done anything she wasn’t supposed to do: affectionate Mother, routinely and concentratedly over many years inculcated upon Eve, from a very young age, that if she ever kissed a boy she would become pregnant, and, as if this wasn’t enough, the warning always came with the consequence: her stomach would grow and grow with a baby inside and she would explode— and die! Of course, Eve, precocious little thing that she was, would eventually find out before she left junior school how babies were really made, and although she knew kisses could not bring about a pregnancy her mother’s educational efforts had a lasting effect and she always rejected boyfriending in the amorous terms. But apparently psychologically scarring your child wasn’t enough of a parental precaution, and as soon as her budding breasts started to take a more shapely form and fill her blouses in the thirteenth year of her young life, and as soon as she had swapped out wide pleated skirts for tight pencil skirts, Father became psycho-irrational, accusing her of being a slut; his undue distress at seeing her body begin to shape into a young woman was expressed through constant anger, but she didn’t know this (nor could she do anything to stop her developing body had she known), and even worse were the beatings where she would do everything she could to protect her head as he angrily exclaimed he had to make her less clever. Social Services had taken her to a home where she found Father’s beatings (though inexcusable) paled in comparison to the monstrosity of abuse some of her coevals had suffered. With her brothers and Mother along with Father crammed into a very small office where files were piled high on desks, during one of the rare visits he had been allowed at the home, and in a flood of emotional tears, in a blubbering display of his utter regret and compunction over how he had treated her, he promised if she retracted her statement and returned home he would never hit her again. She, not enjoying the stay at the home where no privacy existed, living with many other children of differing ages whom shared the facility, gave it serious consideration and, much to her Social Worker’s dismay and disapproval, claimed in court that he had never hit her and wanted to live with her parents. Seemingly, the Social Services intervention had worked, he stopped beating her. Alas, this was to be the biggest mistake she had made in her young life, but one she would only realise after arriving in Yemen which was supposedly to be a brief, two-week holiday.

Having made their way by car from the capital Sana’a to the city of Taiz, they stayed overnight at the latter. It was there they were informed of being from a village to which they departed towards early in the dark morning. Asphalt roads ended and they travelled over dirt roads; nature was becoming more abundant and manmade structures ceased; they drove through rivers surrounded by trees on both banks and were told by the driver whom spoke English it was called Wadi Rushwan, parts of it were more swamp than river; they continued driving through the river for a long while with the murky grey water splashing up the sides of the car before crossing out of it and back onto dirt roads which then turned into partially rocky terrain. Eve noticed on some hilltops castle-like houses stood, some in clusters others solitary, and she assumed its dwellers lived lonely lives.

As the road became rockier and steeper the car shook along and soon they were surrounded on either side by exotic plants and shrubs they had never seen before, Eve and Yusef reached out and plucked different leaves to examine. It wasn’t long before they ascended an even steeper path, to the children it seemed the car couldn’t possibly go up such an inclination and uneven terrain, the area was void of vegetation and this path took them to a mountain of which the route tightly hugged to one side. From Eve’s seat she could see how much they ascended and it was a breathtaking view of thousand feet drops and mountain tops left behind. The car no longer drove, but had become a crab clawing sideways, as the driver skilfully, slowly and carefully made his way up slabs of uneven stone and over rocks and rock outcrops, they only lost traction once and rolled backwards (a round-eyed goodbye-to-the-world feeling of expecting to die gripped everyone, bar the driver) and downwards, but still the children found this challenging, adrenaline pumping journey a thrill. Four and a half hours later the scenery had changed, rectangularish pieces of land, a giant’s staircase, went up and down mountainsides in every direction. The mountains were jagged and grey, the plunging gorges fathomless, the paths filled with large scree, it seemed uninhabitable, but there were houses perched on peaks.

Eve got out of the car viewing the stunning environment, to her right a rocky hill with small shrubs in its niches, above it a derelict house built of stone. Behind it a high cliff rose with a wall erected at its top, the colour of the stone the same as the boulders. From behind the wall, the top half of two houses could be seen rising above, the first house looking much older and different than the second and beside them, massive boulders dwarfed the houses. Eve went to the other side, rocks moving under her Dr. Martens she held onto the vehicle with one hand to keep balance. A path led downwards towards the west, disappearing behind a rough outcrop of rock, appearing again further down then it disappeared behind a rocky hill. To the left, agricultural terraces of varying size, at different levels, went down and up, some bordered by the higher mountains, some bordered by a few houses. Palm trees, acacias, zizyphus spina Christi and plants unidentifiable were dispersed in areas. To the southwest a huge gorge before she saw large layers of land bordered by manmade lines of rock. She looked up and across the chasm to see mountainside to the higher southwest with three houses aligned together at its top, and behind them even higher mountains with several houses dispersed over them and then the sunny blue sky; a swell of breath inflated her lungs as she realised this was going to be a terrific start to travels which she had planned to make when she would be a few years older and be able to travel alone, her world had become even vaster and she was going to explore every beautiful part of it. Eve returned to the right of the car and opened her mouth to say something, but was cut short by the sound of loud gun shots, ducking as did her brothers, pressing their bodies against the car.

“Don’t be afraid,” said Mother, touching Eve’s head, “They’re not shooting at us.”

Eve looked up the steep, rocky path to see four men in brilliant white dresses at the top, each man holding an automatic rifle; arms raised, shooting upwards while looking down at them, due to the hazy effect of the heated sun they seemed to shimmer in their brightness and whiteness.

“Morad?! My son Morad!” Mother exclaimed with delight.

Eve looked up to see her eldest brother whom she hadn’t seen in years, also dressed in white, trying to come down a semi-worn path in the hillside below the old house. He lifted at his dress revealing white trousers made of the same material, as he slipped, twice, landing roughly on his bottom. Morad hugged Mother and kissed her on the head then turned to Eve, hugging and kissing her more than he had his mother for he loved Eve dearly; he constantly bragged about her success and probable future in front of his friends and colleagues in Saudi.

“I thought you were in Saudi?” Mother asked with a big smile, happy to see her eldest son.

“Things changed since Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait and our President’s statements,” said Morad “It upset everybody and things turned for the worse for Yemenis so I decided to come home to my country.” He held Eve’s hand to help her up the steep path filled with rocking scree and looked back at Mother, “And I’m married.”

“Married?! Married to who?” asked Mother, shock blanching her face.

The men continued to shoot as the family made its way up the steep, the boys kept falling so Mother helped Yusef and Father helped Sami. At the top of the steep known as Barh Salliya, Father hugged and kissed with the men, then Mother did the same. Morad introduced his siblings in Arabic, they recognised the mention of their names. One of the men, Uncle Salem, smiled at Eve; his silver incisor and gold front tooth glinted in the sun, he hugged and kissed her as did tall fat and white Uncle Yahya. Super-skinny Uncle Suleiman would not let go of her, hugging and kissing her, smiling at her with paternal warmth; you could tell he worked long and hard in the sun from his weathered skin. The fourth man, Abdulrazaq, was a neighbour; though he shook hands with the rest when Eve followed he just stepped back and looked away which she found to be rude, but this must be their custom here (if only all men, including your groom, would have ignored you so). Inside the newer of the two houses, while her brothers chatted, she noted there was no electricity as she examined a kerosene lantern hanging from a wire in the ceiling.

Now from this day forward and up until the wedding, there would be series of unforeseeable, and unfortunately inauspicious, shocks which would bombard our brave young naïve Eve, and her brothers. To begin with the mildest: they only became aware the only person, other than they, who spoke English was their elder brother Morad—a disadvantage, especially if your parents had neglected to teach you, or even ever talk to you, in Arabic. The handshake consisted of someone extending to you their hand, they pull it forward and kiss the back of your hand, they push it back to you and you kiss the back of their hand, they pull your hand forward and kiss the back of your hand again before releasing your hand and kissing the pads of their own fingers; now repeat this with over two hundred visitors whom arrive within hours all excited to see you (how exhausting). The women, girls and children made rows on the ground all the way to the opposite wall; the older women wore zigzag dresses of different fabrics, tight at the top, but baggy at the bottom, a symmetrical zigzag pattern sewn onto both sides of the chest with a zip in the middle; the bodice seamed to a long flowing skirt, their hair completely covered by black veils either bound like a turban or tied around the forehead and over the ears. The younger women and girls wore square-cut neckline dresses showing cleavage, only the back half of their hair covered by a head veil, black, but with coloured or sequinned borders or corners, loosely hanging off the sides pinned into place by bobby pins, they all had their hair parted at the middle or from the side. Everyone wore green or blue rubber flip flops, many children walked barefoot. This wall of curious visitors crammed full of the Bawaba, gazed at the children without communing with them as if they were some odd spectacle; whenever the three British children tried to communicate the visitors laughed raucously at the sound of their strange, foreign language so Eve read the book she had been gifted by her brother at the airport, a supernatural novel, but this in itself caused a stir with the women pointing at it, and Eve, as if she were exhibiting some strange, unacceptable behaviour; but even the book did not cause as much stir as did her blousered body, trousered legs and uncovered, cascading dark brown hair.

Then came Uncle Aref, a thin dark young man whom swayed and sauntered as he walked, and had not an iota of the kindness and jollity of his brothers. Why, he furrowed his eyebrows and glowered at our already uncomfortable and out-of-place Eve; he didn’t want her wearing trousers, he didn’t want her wearing blouses (no he did not want her naked), he didn’t want her reading books! In fact, he made such a hullabaloo out of her very modest attire she was begged to change by Morad and Mother, which led to her wanting a shower, which brought to the siblings’ awareness there was no running water in the house, there was not even a bathroom, let alone a toilet as in the sense of a ceramic throne. Had Father prepared them, instead of lied, about the reality of the village: no water, no electricity, none of the basic norms you think you can’t live without, it would have been kinder of him and the shock more gentle, but he had seen their extreme disappointment at the quality of the hotel rooms and worried if he gave them a true account of what he had described as a beautiful farm with horses (with the promise of choosing the best horse for Eve to ride (turned out she’d be the one ridden to the euphoric finish line)) and all the utilities and facilities of modern life they needed—well, he believed he would not be able to get them anywhere near the village and then all would be lost. It has to be said, they were lucky Morad had arrived a few months prior to their arrival, as when he’d returned after long life in Saudi there were only boulders to hide behind and hope no one trespassed upon you, which hadn’t proven to be the case for Morad too many times with shocked, shy women peeping at his impressive exposure through splayed fingers covering their faces, hence the humble privy-cum-bathroom was built: a three by five foot building located outside and below a path: Eve felt how terribly wrong she had misjudged the toilets in the hotels of Sana’a and Taiz which were Asian style: basins embedded in the tiles of the floor, they were not holes, but this was definitely a hole in the floor complete with two jagged rocks on either side to place your feet on. Then came the day when Father informed them there was no going back home to Britain—this was their new home. Their passports had been stealthily confiscated, money surreptitiously taken away, and all vehicle owners and their families were given instructions that these three children were never to be allowed to board a vehicle unless accompanied by Father or an Uncle. The children had tried to discuss the situation with Father because rationale and discussion were the key to solving unexpected issues which suddenly popped out of nowhere with the threat of life-changing consequences, but when Father, with his newfound dictatorial attitude as there were no Social Services to answer to here, simply brushed off their oh-so important reasons pertaining to returning home: Yusef had college to return to; Sami and Eve school and exams; they had their friends to see, their lives to live; in exasperation Yusef said he would call the Embassy, in protest Eve said she would call the police—this only tickled Father pink, he laughed while telling them here in these mountains there were no embassies or police; and even if they had been in the city, well, this was Yemen: they were his children and not even the authorities have the right to get involved. The children were left with a disorienting feeling of being trapped: their minds and hearts still felt free, they were free, but they could not leave this village due to Father’s instructions and the remoteness and perilous terrain; freedom, like good health, you don’t notice it until it’s gone—or, in freedom’s case, taken away.

Eve quarrelled with Mother over Father’s claim, and she demanded immediate departure, but after upbraiding her daughter Mother, looking much embarrassed, sat back with the other women, talking in Arabic as they turned their hands up and tutted, and held their cheeks in disapproval. Mother kept glancing at her with a lot of uncalled for disrespect, and it worried Eve that Mother be flustered because she wanted to go home, instead of being upset about her husband claiming they would not be returning. Eve threw herself onto the bed, crying, hating they had come to Yemen; she hated she had believed her father’s lies; she could not stand the look of angry embarrassment on her mother’s face and she hated that she was crying in front of a room full of strangers. A distraught Morad sat on the bed trying to comfort Eve, but all she wanted was to be taken home. At this point an old woman walked in, wearing a deep purple zigzag dress, a black veil tied around her head, turban style and unusually larger than everyone else’s. She nodded her head and raised her hand towards them then sat with the women on the other side. She got up and stood a yard away from Eve, watching her cry; she turned her hands up and held her chin several times then turned towards the women saying something, very loud. Mother replied, giving Eve the stink-eye.

“What did they say?” asked Eve.

“She asked why you’re crying,” said Morad “And mother told her it’s because you want chocolate.” Eve felt insult bloat in her stomach, and the immense humiliation being accused of such a childish want had mixed with fright.

“I don’t want chocolate!” she shouted in anger “I want to go home! Take us home!” and started crying again. When she calmed and lifted her head she was met by Purple Dress Lady whom had come closer, still watching her intensely and with much fascination as if she were something to be studied. The lady said something to Eve using a lot of hand movements, and every time she made her exaggerated gestures while talking her thick gold bracelets clanked and the waft of her sickly-sweet, strong perfume hit Eve in the face. Eve didn’t care to know what she was saying: she felt lost and was more concerned about how soon they would be back home so she looked away, hoping the lady would leave her in her misery. Mother got up and spoke quietly to the lady whom turned to Eve, standing even closer, extending her arms, her hands almost reaching Eve as she spoke.

“Are you happy now?” said Mother angrily at Eve, “She says you’re wild! She says you need to be tamed!”

Eve, though not a vulgar girl, rarely used swear words, unless in jest or in extreme anger; as you can understand being referred to as an animal causes the latter emotion; to put it into a less vulgar rendering than what she used, she asked her brother to translate to Purple Dress Lady to ‘copulate away’ (needless to say in this ultra-conservative culture, her brother did not translate his sister’s message, but told the old hag his sister was upset about leaving home).

The sun hung low in the west, using Morad’s binoculars tiny outlines of cargo vessels could be seen in the distance, silhouettes in a shadow-show. The children could make out a mass of land appearing on the curve of the horizon, Morad said it was the Horn of Africa. They watched the orange balled sun set in the sea from in front of the Second House, and still they didn’t believe what had been said, that they would not return home. As it became darker, kerosene lanterns were lit and its yellow-tongued flicker gave a haunting illumination to Uncle Suleiman’s face as he told stories of demons and beasts.

The next day more visitors arrived in the afternoon: women and children. Eve looked up from where she sat upon an elevated king-size bed covered by a sumptuous blanket with images of two angry, roaring tigers woven into it, to see a teenage boy walk in, to her surprise he wore extremely fashionable female black trousers with a colourful sash around the waist and a white Peter Pan-collared blouse. She did a double take and couldn’t believe her eyes—he was wearing her trousers and her blouse! She jumped off the bed and demanded he tell her why he was wearing her clothes and how he had obtained them (had she known he was the local catamite for the paying non-locals at night, she wouldn’t have requested their return), all he did in response was grin like a fool, while the guests laughed at her strange language. She went outside and called for Father and Morad, Uncle Suleiman followed them down wearing her baggy embroidered white blouse with engraved silver buttons seemingly unaware how ridiculous he looked with it too short on his long torso, too tight around his chest with the buttons ready to fly off. When Morad explained to him Eve’s upset he merely smiled a yellow smile and embraced her in a hug more like a headlock and kissed her head; she could smell the not unpleasant brewy odour of a green substance stuffed in his cheek which was seeping onto his canine tooth; pointing to the shirt he wore he said something, then slowly shook his thick finger in front of her face; Morad translated: women don’t wear trousers or shirts, she wouldn’t be needing them. On inspecting her suitcase she found all trousers and blouses gone, given away to boys; her skirts and dresses torn to pieces, material had been sent for to be sewn into square-cut dresses, they were beginning her acculturation into becoming one with the nation of this village where all girls and women wore the exact same style of traditional clothing and hairdo.

Like all surprises, the greatest is better left for last: Father’s final fateful changes to their lives imparted upon them was to be the most devastating. How does a girl who only dreams of playing with her friends, excelling in her exams and living a carefree life respond to being told she is to marry Uncle Suleiman’s son whom she has never met before, currently working in Saudi Arabia? Well, first she thinks it’s a joke, she and her brothers stare at Father bemused, their minds totally unaccepting what they have fully understood; then she goes on to enquire when they will be heading back home because she needs to resume her education and misses her friends; and when Father (brute of a man he’s turned out to be) makes it unequivocally clear that she is to marry an adult, disregarding her tender age, an asthma attack hits you full force. And when you recover, you find out nothing has changed; you will still be forced to marry, but at least Morad provided comfort and salvation, with a worried and sympathetic face he told her if she did not want to get married all she had to do was say no right now, and he would not allow it to happen so she gave her brother the reply: an unequivocal, unmistakeable, absolute NO.

The following day Eve came to learn her family was moving to an area in the lower flatlands in the West called The Dibt; all, except Morad who would remain in the mountains, were leaving together; and she was left behind without being told why, to follow shortly after they arrived there. Sitting in the cool morning sun on the ducka outside, surrounded by both exoticism and eccentricity, Eve reading her book felt lonely without her brothers. Uncle Suleiman came out of the First House carrying a thermos flask of tea, Dawood his eight-year-old son (he had in total five sons and five daughters ranging in age from adults to toddlers) followed with three glasses and a can of condensed milk especially ordered because Eve didn’t drink tea without milk. Uncle Suleiman squatted on the ground in front of Eve and watched her intensely, unnerving her with his stare; he was deep in thought, she could see that; his thoughts included her, she could feel it. He wasn’t just watching her, but with quiet smugness measuring, looking at her and imagining, seeing what the future could be and how different his life would be as he stroked his short beard with the back of his index finger. A brief lupine-smile flickered in his eyes, on the corners of his lips, as if he’d won some prize, but he stifled it. Dawood poured himself tea and went off towards the stables. Uncle Suleiman smiled and smacked his lips as he drank the tea, when he finished, he spoke to Eve, she didn’t understand though it was obvious he was trying to be very nice— maybe because her family had left. He reached into his pocket and pulled out a pretty small heart-shaped box and seating himself next to Eve, holding her right hand while he smiled and talked, he slipped a gold ring full of gem stones onto her finger. He pointed at it, lifting her hand with his closer to her face. She removed it from her finger and placed it in his hand, but he got up and bending over her tried to get the ring back on her hand by force, speaking loudly.

“No!” she said, hiding her hands in her armpits. He went into the Bawaba and returned with Morad and Dhalia.

“He wants you to have this ring,” said Morad “It’s from his son, the one they want you to marry.”

“Tell him I don’t want the ring, and I don’t want his son.” said Eve.

Morad translated. Dhalia frowned and walked away; Suleiman shook his finger at Eve and gave the box to Morad; glancing at Eve he spoke with half a smile, half a smirk before slowly walking away.

“He wants me to send it to Dad.” said Morad.

Upon arriving at The Dibt she found though it was easier to walk around on level ground, it was actually a harsher environment with less food, less shelter, a more oppressive sun, an even more oppressive Father, and the unbearable heat and damned mosquitoes were a terrible combination. Not long after her arrival, her brothers were sent back to the mountains while she remained with Father and Mother at Uncle Faris’ house in The Dibt. It was during these weeks before she would see her brothers again (and only glimpse them briefly at that on the wedding day), that he returned to violence in a bid to break her spirit, wanting her to marry Adam, Suleiman’s son whom she’d never met nor wanted to meet, willingly (who needs pre-marital counselling for couples when you can beat them into compliance?). He beat her, threw things at her, belted her, took her out into the pitch-dark wilderness and left her there, but her answer always remained no. His last act of violence, making her believe he was about to cut her throat with her head pulled back asking her if she would marry Adam, and she would have said yes out of mortal fear had she been able to articulate, but all that would come out of her mouth was a strange “agh, agh” noise, and upon hearing Mother’s screams Uncle Faris came rushing into the room shouting at Father to fear God and stop behaving like a madman. Father removed the knife from his daughter’s neck and pushed her down to the ground where dirt stuck to her wet face, and he left the room. Uncle Faris scooped up the motionless girl and lay her on the bed, but Eve didn’t notice falling asleep that night, the last memory she forever remembers of that terrible day was the taste of her tears mixed with the smell of damp dirt burning the back of her throat.

The next day Uncle Suleiman, his son Adam, both carrying a metal trunk full of presents for Eve: fabrics, perfumes, money, sweets and other trinkets; accompanied by a group of men including ‘The Ameen’, the person responsible for writing out official documents, arrived by car. From outside the door, Eve refused to say yes; nonetheless The Ameen (the noun which is derived from the word trusted, honest, integrity, safe-keeper) wrote out a marriage contract not only stating she had consented to the marriage, but also added three years to her age to take it well above the legal marriage age. Adam tried several times to get close to her, his mien was both excited and happy (Eve had had the same countenance when Father had allowed her to buy a kitten), as talking was out of the question with her not knowing Arabic and he not speaking English whenever he said whatever it was he was saying was followed by awkward silence; but whenever he smiled she reacted as if he’d flashed multiple rows of canines through an unlipped leer; and every time he attempted to get closer she would leave the room or area, but he kept appearing after her.

The day of the wedding her heart filled with worry as she poured water over herself and shampooed her hair and lathered her body, she couldn’t stop fretting over why Morad had even allowed them to come and ask for her hand in marriage, he was going to object today. The Uncles Faris and Nageeb slaughtered a goat in front of her while she, seated wedged between two young female cousins on a bed which had been brought outside, covered her eyes, it was some sort of sacrifice. They proceeded to put goat blood on her forehead which she mistook as them wanting her to drink in some sinister Satanic ritual to which she leaned backwards on the bed and kicked with all her might to keep Uncle Nageeb and his sacrilegious blood away from her; Father and Mother laughed while Father explained they didn’t want her to drink it—just to purify her by putting some on her forehead—they ended up having to wipe it on her feet as she continued to kick like a cycling kangaroo on drugs, before Mother soaped it off. The marriage convoy arrived with the men and women from the mountains. Uncle Suleiman’s married daughters, Dhalia (married to Morad) and Latifa (married to her cousin Hammed), arrived in a cloud of perfumes, both wearing sparkling, brightly coloured dresses; donned with so much golden jewellery it could be mistaken for armour; the backs of their hands were covered in black patterns, their palms and finger tips dyed with henna, orange and dark brown. Smiling and emitting ear-piercing ululations, they took Eve by the arms as she asked about Morad’s whereabouts, and they changed her into a dark green dress picked out from the large green gift trunk painted with golden mosques. They attempted to pattern her hands with black dye while two women sang in antiphony at her feet, one extolling the bride’s beauty (highly exaggerated), the other praising the groom’s handsomeness and wealth (slightly underestimated), while the child-bride wept in large sobs which shook her small frame; calming only when Morad entered to sit beside his bewildered sister, only to devastate her that he could not stop the marriage because Father swore to kill her if she didn’t go along with the wedding. She cried until she could cry no more, and a different panic set in, whenever Dhalia and Latifa moved her from room to room she could not feel her legs, they belonged to someone else—it was not she that was walking, the eyes looking back at the bustling crowd, all gathered to celebrate the ‘happiest day of her life’, did not belong to her, she felt removed and though she knew her body was moving, her soul seemed to lag behind and follow it around instead of being in one being. She never knew a wedding could be this noisy and disarraying. They changed her again into a different dress, this time made of white fabric with three scalloped black frills going across the chest with tinsel green, pink, gold and silver flowers stitched into them, the remainder of the bodice and beginning of the skirt were white and the frills with tinsel flowers followed in layers from the knee to the hem; they sprayed her hair, neck and chest with so much Rumba perfume her head began to ache; Aunt Hasna brought an incense burner full of glowing, hot embers and broke pieces of bukhoor into it and with perfumed smoke anointed Eve’s body, dress and hair until she coughed before they took turns incensing themselves; they piled heavy gold around her neck and pinned the rest to her chest, attached jewellery to her fingers, wrists, and she sighed as they affixed large, heavy earrings to her earlobes, as if the weight added to her already burdened soul, the dangles of golden beads of which tickled her neck every time she breathed heavily or turned her head. Women and girls took turns energetically dancing in pairs while the other guests threw money from over their heads. Mother returned to the room and leaning against the wall put a shaking hand to her own mouth and squeezed, her face red with sorrow, she cried painfully and it would be the only sign of regret she ever showed towards her daughter’s marriage, giving Eve a faint glimmer of hope, maybe her mother would not allow this travesty to continue, but instead she told the others to get her ready. Latifa tied a large, flowing shiny black pleated skirt around Eve’s waist; Dhalia threw over Eve’s head a black hood made of the same material, it too was large and flowed overlapping her waist. Eve cried and trembled, still hoping Morad would prevent the marriage.

And now Eve stood facing Father beside the car, begging him with all her love for him, with all his love for her, for the sake she was his daughter, for her life, not to let this happen. But with a threat issuing from his mean thinned lips he and Morad lifted her and bundled her into the car next to the groom. And as the car rolled on, she saw her brothers standing under a rickety shelter with Mother behind them, all three crying; and she watched Father crying so hard his head and shoulders bobbed violently, and the two black chiffon veils sewed into the hood of the sharshaf fell lightly over her face and black tears rolled down from her kohl-lined eyes.

[Want more? Click below to read a longer excerpt.]

Praise for the Book

“Ms Ayoub wrote about forced child marriages in this book to bring awareness and help towards ending this atrocious act. […] I can't stop crying my eyes out.” ~ Jennifer (Jen/The Tolkien Gal)

This is one of the most gripping, harrowing stories I’ve read, and I could hardly put the book down. […] What adds still more power to this story is that it is based on Ayoub’s own life. She was a child bride, and she now writes this book as a survivor. I came away from the book in awe of Ayoub’s personal strength and endurance.” ~ Neil Couler

“I am very, very impressed by Miss Ayoub's first novel.” ~ Jaclynn

My Review

By Lynda Dickson

The story begins in the midst of fourteen-year-old Eve’s forced wedding to Adam while supposedly on a family holiday in Yemen. Eve is a studious Welsh girl with dreams of going to university to study law. She thought “this was going to be a terrific start to travels which she had planned to make when she would be a few years older and be able to travel alone.” How wrong she was. Stuck in a place with no running water and no electricity, her passport confiscated, and repeatedly raped by her new husband, Eve is virtually (and sometimes literally) a prisoner in Yemen. We follow her over the years as she tries to escape her situation by running away or getting a divorce, only to be met by obstacles every step of the way. Will Eve ever gain her freedom and, if so, at what cost?

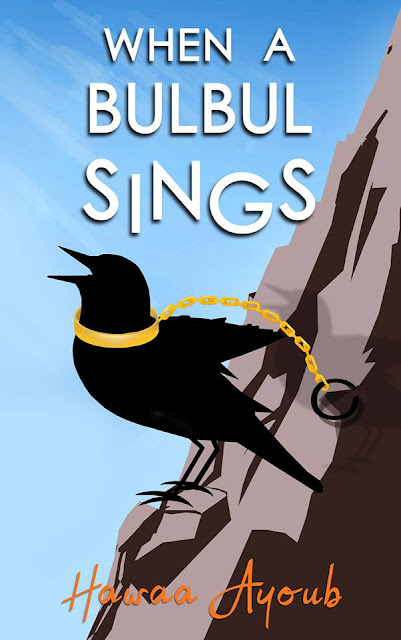

The title and cover art reflect Maya Angelou’s I Know Why a Caged Bird Sings and its inspiration, Paul Laurence Dunbar’s poem “Sympathy”, with their themes of oppression and yearning for freedom. The literary writing style won’t appeal to everyone, but I found it multi-layered, engaging, and full of rich vocabulary. Unfortunately, there are also numerous editing errors, including the constant misuse of “whom” and consistent punctuation errors in dialogue. The author, as omniscient narrator, speaks directly to the reader and Eve, making astute observations and throwing in her parenthetical comments along the way. She gives us a fascinating glimpse into the lifestyle and traditions of the Yemeni people and offers us a collection of vignettes in which we learn about Eve’s day-to-day life: her experiences learning Arabic, finding snakes in the outhouse, the ongoing drought, farming life, raising rabbits, teaching English, and the difficulties of fetching firewood. I especially enjoyed the story about the lightning strikes. The author also uses Eve’s story as a platform to inform us about more serious matters, such as the plight of child brides, the true teachings of the Quran, gender roles, and female circumcision. Eve alternates between humor, hope, despair, bouts of depression, and resignation, as “everybody in her life who was supposed to aid and protect her, love and shelter her, had effectively abandoned her.” Her story is all the more harrowing because it is based on the author’s own experiences.

A touching story of survival against the odds.

Warnings: sexual references, sex scenes, genital mutilation, child abuse.

Some of My Favorite Lines:

“Oh, how she missed books and reading terribly!”

“… just as hunger had the magical power to make a dry, unchewable piece of bread taste as sweet as honey, book deprivation had made any book an intriguing read.”

“She learnt Arabic herself and now she can speak like a bulbul sings!”

“They say when a bulbul sings it’s to forget all its problems, because when it sings the sound fills its head with beautiful thoughts so there’s no room left for its worries, but its song can also make people forget their problems too.”

“Eve’s the only girl I know who can use religious sayings to prove a point against what a man says.”

“Maybe it’s still difficult for her to live here, maybe she longs to go home so she sings like a bulbul to forget…forget where she is, forget where she used to be. Forget her pain.”

“… this happiness only lasted for as long as she could sing. Once she had stopped singing, her eyes once again saw the four whitewashed walls of her room, she stood still as if expecting some magical force to transport her back home. When this didn’t happen, all she could feel was a wrongness eating at her soul: the wrongness of an innocent man jailed for a crime he didn’t commit; the wrongness of a bird born to fly and be free, caged for the pleasure of its owners, its captors.”

“A man is like a dog—if a woman pats her lap he will come panting, but if she raises her arm and shoos him he’ll run away. So if a woman wants a man she can lure him, and if she’s chaste she will chase him away and he won’t dare come back.”

About the Author

Hawaa Ayoub, author of When a Bulbul Sings, has experienced the traumas of forced child marriage first hand. She hopes to raise awareness through writing about child-marriage.

She lived in Yemen for nineteen years, the first eight years in a remote region whose inhabitants hadn’t changed their way of life since ancient times, in an area at the time inaccessible to outsiders including Yemenis from outside the region.

When a Bulbul Sings is her first novel.

She writes about forced and child marriage in a bid to raise awareness to help towards ending child marriage in Yemen and other countries where millions of underage girls are either forced or entered into underage marriage. Having gone through forced child marriage to an adult, Hawaa Ayoub knows the child-bride not only suffers the traumas of rape and being rudely thrust into the adult world, but a child-bride can also live with the psychological, emotional and physical consequences throughout her life.

When a Bulbul Sings is an objective story where the aim is to explain, highlight, and criticize forced and child marriage.

Links